23.04.2019

Chikankaari—the art of hand embroidery from Lucknow, Central India

When one walks through the narrow streets of Lucknow, the capital of the state of Uttar Pradesh in central India, one would notice the strong Mughal influence evident in the architecture all around the city. The intricate jaals or mesh-like structures, paisleys, floral creepers, and elaborate archways draws one’s attention. The city is known for many art forms as it is known for its textiles. Like many other textile art forms of embroidery which are region-specific, the art of chikankaari is associated with the city of Lucknow for the past many decades. In India, embroidery is mainly practiced by women as a part of their daily activities performed at home. Chikankaari is mainly a white on white shadow embroidery which traces its origins back to the Mughal times.

A scan of sheer white Chikankari textile developed by Injiri in 2018 in Lucknow. The swatch consists of several stitches, some of them being; jaali (perforated drawn thread embroidery) visible in the big leaves on either side outlined by dori. Bakhia (shadow work) in the flower petals in combination with hool (eyelet stitch). A kind of satin stitch locally called the Channa patti is used in the smaller leaves.

A scan of sheer white Chikankari textile developed by Injiri in 2018 in Lucknow. The swatch consists of several stitches, some of them being; jaali (perforated drawn thread embroidery) visible in the big leaves on either side outlined by dori. Bakhia (shadow work) in the flower petals in combination with hool (eyelet stitch). A kind of satin stitch locally called the Channa patti is used in the smaller leaves.

It is believed to have existed in India for about 400 years and is said to have originated from Persia, brought to India by Noor Jahan, the wife of Emperor Jahangir. Tracing back through history, there are various viewpoints where some said that this technique developed as a less expensive imitation of the Jamdani from Bengal while others said it developed under the patronage of the Mughals in the Royal courts of Lucknow.

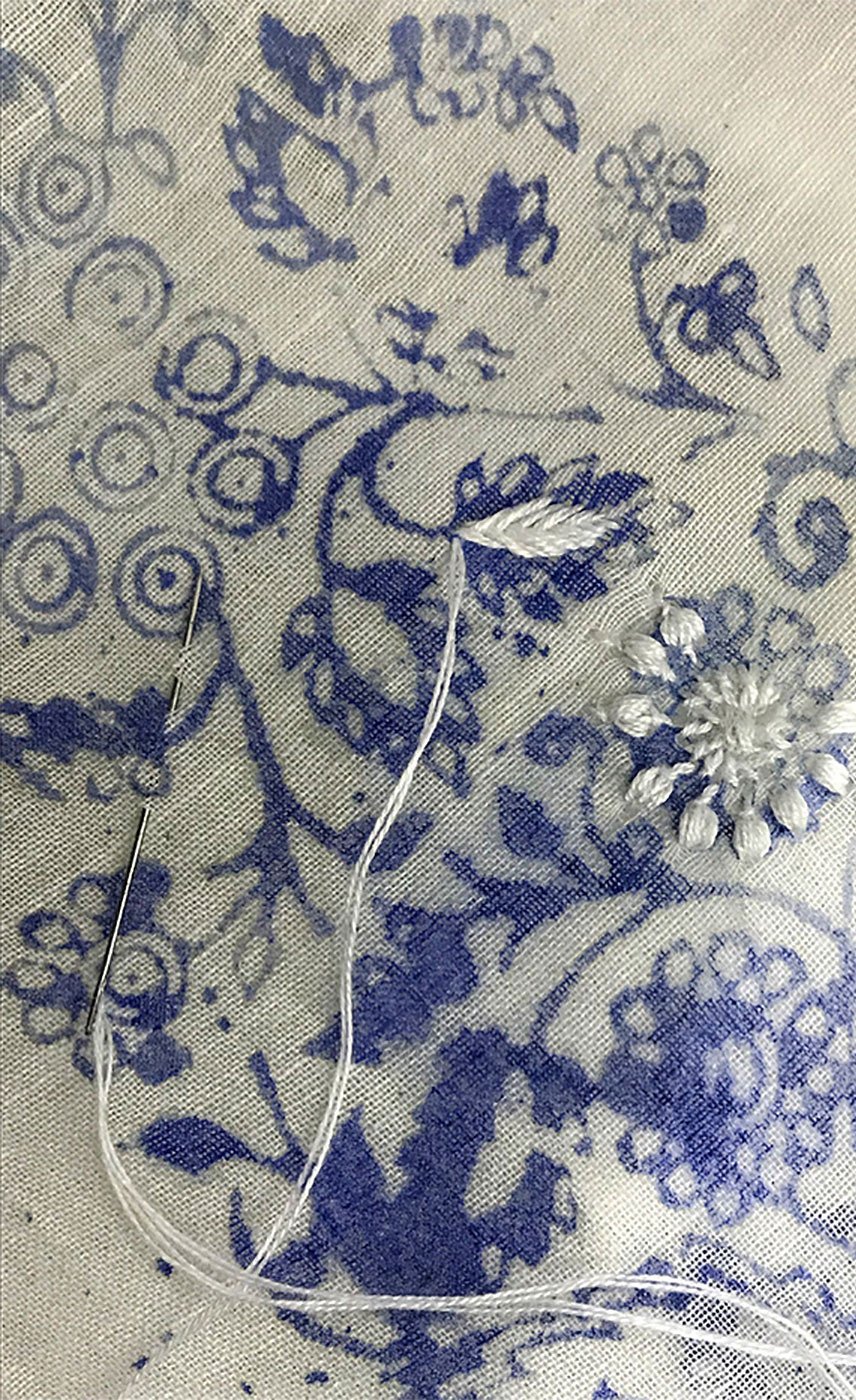

Beautiful dense compositions of Mughal floral patterns often incorporate intertwined creepers, flowers, intricately embroidered paisley motifs called keiri, tiny buds, tendrils, leaves mostly the paan leaf, a status symbol in Lucknow and the fish motif make the Chikankari garments exquisite. As mentioned earlier, the craft is a cottage industry and is practiced mainly by women from a young age. The way it works is that middlemen who work with stores and businesses hand over bels of sheer white fabric printed with fugitive colours, to the embroidery artisans all around Lucknow.

Above is shown a Chikankari artisan carefully embroidering the design on printed fabric which is stretched on a wooden frame, the leaves are being filled with the channa pati stitch.

Above is shown a Chikankari artisan carefully embroidering the design on printed fabric which is stretched on a wooden frame, the leaves are being filled with the channa pati stitch.

The ladies work on these fabrics during their leisure time, once all the household chores are completed. On closer observation of these fabrics, the designs printed on them become evident, guiding these women in embroidering it. These designs are block printed by temporary dyestuff by a separate group of people in Lucknow called the Thappakars, the block printers.

The block makers situated in various locations within Lucknow carve exquisite designs in Indian rosewood and brass. A mixture of neel (synthetic indigo), gond (gum from Babool) and water is used to imprint the designs on the fabrics. Once these fabrics have been embroidered, they are washed, starched, dried and ironed, ready to be delivered to stores. Traditionally, the chikankari that was practiced during the Mughal times was way more intricate making it expensive and allowing only the nawabs and royal families to commission these pieces. Also, the garments were hand-sewn along with being embroidered. The hand sewing allowed the maker to do each piece at leisure and it was not just a craft form but an art form.

The image above depicts a printed surface; the fugitive gum used in the process has permeated through the fabric onto the base cloth, leaving a memory of the process. The image on the right shows a tray containing a mixture of neel, gondh and water, ready to be used by the thappakars for printing.

The image above depicts a printed surface; the fugitive gum used in the process has permeated through the fabric onto the base cloth, leaving a memory of the process. The image on the right shows a tray containing a mixture of neel, gondh and water, ready to be used by the thappakars for printing.

However, at present, the garment is machine sewn before sending out for Chikankari work less expensive and cost-effective. The garments and accessories made from these were mainly Jamas, dopali caps, angarkhas (an overlapping upper garment), chapkhah (a fitted coat), achkan (a long robe) and kurta (a long tunic) during the times of the Nawab. In the present market, one can find basic tunics, shalwar kameez, sarees, and dupattas.

As the market changed, the technique evolved to become simpler and the number of stitches reduced from 32 to 5-6 commonly practiced ones. The time consumed to make highly skilled pieces is so high that the mass market is unable to afford the cost of making and finding the right consumer for exquisitely embroidered pieces. Therefore, the largest part of chikankari production uses barely 4 to 5 stitches and is usually the least time-consuming one. The present market is full of low cost, poorly embroidered ready to wear products.

There exists a smaller segment of the market where people are trying to retain high-value skills in the work that they do. Often this market is for the niche group of people who appreciate the highest form of chikankari. The finely and leisurely made pieces consist of a variety of stitches like tepchi (running stitch), rahet (stem stitch), bakhia (shadow stitch), janhira (chain stitch), kat (blanket stitch), murri (satin stitch), ghas patti (inverted fishbone stitch), hathkati (openwork) and jaali (pulled threadwork to create perforations).

Chikankaari on muslin khadi is a technique Injiri work with every season. White on white embroidery is beautiful and one of the quietest forms of embellishments used by Injiri.

Above is shown a Chikankari artisan carefully embroidering the design on printed fabric which is stretched on a wooden frame, the leaves are being filled with the channa pati stitch.

Above is shown a Chikankari artisan carefully embroidering the design on printed fabric which is stretched on a wooden frame, the leaves are being filled with the channa pati stitch.